There is an evolution occurring in a gentle but inexorable fashion in O and G. The generalist model is being refined as the academic complexity and skill-base of gynaecology expands. In the capital cities and some major provincial areas, four major types of private practice are evolving. Obstetric group practices with 24/7 in-labour ward coverage are balancing lifestyle demands with the ethical and medico-legal obligations of high standards of care. There are a growing number of office-based gynaecology practices who perform day surgery and procedures such as colposcopy, but refer advanced benign surgery to operative gynaecologists who are mostly laparoscopic surgeons. The collective fourth group is the various subspecialty practices. The rise of the operative gynaecologist represents a significant ‘sea change’ in our specialty. In recent but past times, busy operative practices were mostly senior gynaecologists, who after half a lifetime of obstetrics honorably retired to surgery, mostly repairing prolapses from an era of vaginal deliveries. Now, many of our seniors reduce their stress by providing expert office consultations and refer their surgery to a younger laparoscopically-trained surgeon.

The time is fast approaching when this trend will need to be formalised in the RANZCOG training program. Procedural colleges such as the College of Surgeons and the College of Physicians have recognised that the one-size-fits-all general degree is now outdated and women’s health should be no exception. The many changes in gynaecology surgery of the past 20 years mean that review and restructure of training is becoming urgent. The urgency is because many consultants are becoming alarmed that registrars are struggling to attain sufficient surgical experience during their training to be surgically competent on receiving the Fellowship and entering practice. Many registrars agree and do not have the confidence to begin advanced surgical practice as they finish their training. These concerns have been validated in a recent study by Obermair et al.1

Why are many registrars struggling to get enough operating?

There are more registrars and fewer lists. Accredited posts have doubled in the past 15 years. In the same period, public hospital operative waiting lists have blown out. Bed numbers have been reduced and operating lists are often cancelled for budget reasons. Productivity has arguably reduced with shorter operating lists, no provision for nursing overtime and an uncertain bed supply up to the day of admission. In Brisbane, the redevelopment of our two major teaching hospitals meant the loss of 600 beds. Operating theatres were merged, streamlined and reduced. Specialty operating theatres for gynaecology adjacent to the ward were closed. Paid working hours for registrars are less meaning that the shift obligations for labour ward take precedence over gynaecology experience. For example, registrars at a major Melbourne hospital only do 12 weeks of gynaecology in their second training (first registrar) year. There are also more staff specialists who, though generous with their registrars, also need to maintain their skill set and therefore compete for surgery. Changes in the international workforce mean that the high volume operating jobs in places like the uK are no longer available.

Our response to this was first to reduce the logbook numbers for the minimum required number of operations and then to accept that these are often not achieved. Registrars should perform 100 major operations and 50 laparoscopies in four years but often can’t achieve even these lowered bars. The operative subspecialties have further shifted surgery away from general specialist training in urogynaecology and oncology. Advanced Fellowships in endoscopic surgery have reduced general specialist opportunities and the higher complexity of this surgery has made supervising consultants more cautious about handing it over to junior registrars. Rural and provincial training opens opportunities, but many provincial specialists worry that the rotational registrars can’t use their time to fullest advantage due to their previous lack of operating experience. Private sector training has increased exposure but often not the hands-on for registrars as the primary surgeon.

The first half of the argument for a restructure of surgical training is that the training is no longer able to achieve its objectives in providing enough complex operating to consistently produce a safe and competent gynaecological surgeon in six years. The second half of the argument is that the very nature of gynaecology surgery and practice has changed for the better.

The emergence of endoscopic surgery has been a revolution in improved patient care. Patients have less pain and faster recovery with comparable or fewer complications. It is the mode of surgery we would want for ourselves, our partners and daughters. A well-trained laparoscopic surgeon will nearly never do a laparotomy. The scope of surgery has expanded for conditions such as endometriosis. The proportion of hysterectomies performed laparoscopically has doubled in the last decade rising to 40 per cent in 2008-09. This has required a major but slow reskilling of the surgical workforce. Whilst some consultants were reskilling, it was difficult to teach the registrars. This is another reason for the separation of surgical skills between the emerging group of operative gynaecologists and their contemporaries. Advanced laparoscopic surgery is harder to do, more intricate and requires a greater investment by hospitals in equipment and infrastructure. A number of specialists have chosen not to reskill and others have never been trained, yet the future is even more complex with the advent of new technologies such as robotics.2

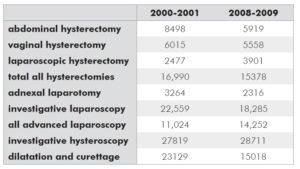

There is also less private sector surgery to do. Medicare data (see Table 1) shows that the annual number of benign hysterectomies has dropped by 1000 in the last decade. Each private gynaecologist can now average about six open and four laparoscopic hysterectomies per year. Laparoscopies are down by 4000 to 31,000. Complex laparoscopies for endometriosis have increased to 1700 per year. Adnexal laparotomies are down annually by 1000. Hysteroscopies are up by about 1000, but dilatation and curettages (D&Cs) are down by 8000. Vaginal hysterectomies are down by ten per cent but vaginal repairs have increased (the data is unreliable with the change in item numbers). This is a reduction of 10,000 a year of our most common operations in just ten years, despite record levels of health insurance, a population increase and a struggling public sector. Much of this change is due to better non-operative management of gynaecological conditions. Further reductions are expected in cervical surgery for cervical dysplasia (CIN) and there is a slow shift of procedures to other specialties such as interventional radiology. Importantly, however, there is a shift of care from the operating theatre to the office.

Table 1. Comparative Medicare data for gynaecology. 2000-01 and 2008-09 financial years.

The future of gynaecological surgery is fewer, more complex cases, done better.

The time has come to stream the registrars for these evolving career paths. General specialist training could initially involve obstetrics, office gynaecology and basic operative training for day surgery procedures. Probably, in time, obstetrics may hive off as a separate specialty. Complex operative gynaecology and subspecialist streaming should occur at an early stage, probably at the end of second year, reducing the obstetric exposure and maximising access to diminishing resources for surgical training. Surgeons, oncologists and urogynaecologists don’t need four years of obstetrics. Tomorrow’s gynaecological surgeon also needs to be trained in basic urology and general surgery.

Whilst restructuring the training to reflect reality needs definitive action, the consequences of this would be gradual and non-threatening. The current group of general specialists will not lose their operating, especially those who have upskilled into minimally invasive surgery. However, over time the differential skill-base and referral patterns between graduated operating and office gynaecologists will result in an orderly market. We should not make the same mistakes as happened with the previous introduction of subspecialisation, where insufficient attention was paid to defining the markets for the new qualifications. We need to pay attention to the political consequences of change as well as the academic requirements. There may be an argument for structuring rebates to ensure the tertiary referral nature of operating gynaecologists, as happens in France. Consultation rebates for office gynaecology may move to those of the physician rather than the proceduralist. It is hard to see any adverse consequences in the public sector which provides both outpatient clinics and operative services.

procedural gynaecologists.’

A special sector that does need consideration is the specialist headed for practice in rural and provincial areas. These doctors need to be multiskilled. We will need to continue to train a general specialist group with advanced operating skills to service the country areas. However, this shouldn’t be too difficult to implement as it reflects the current training program. In fact, more surgical cases should be freed up for this essential training than are perhaps currently available. Office-based gynaecologists who desire a career change could also have the opportunity to pursue Fellowships in complex surgery and alter their practices.

The proposition to formalise the training of gynaecologists for an advanced surgical qualification is neither radical nor threatening. The trend is happening anyway. The current surgical training is too devolved and uncertain and does not represent best use of diminishing case material and experience. We need proportionately fewer, better trained minimally invasive surgeons. We need more office and procedural gynaecologists. There is a fit, both in the use of training resources and public and private practice. This is evolutionary change that we now need to manage and support.

Dr Molloy has a private practice in infertility and minimally invasive benign surgery. He has been President of the Australasian Gynaecological Endoscopy and Surgery Society (AGES) and the National Association of Specialist Obstetricians and Gynaecologists (NASOG).

References

- Obermair A, Tang A, Charters D, Weaver E, Hammond I. Survey of surgical skills of RANZCOG trainees. ANZJOG; 49:1; 84-92.

- Ellwood D. What is the future for gynaecological surgery? Editorial. ANZJOG; 49:2; 119.

Leave a Reply