How does an urban GP make decisions on whom to refer his/her patients for subspecialty gynaecological problems such as urogynaecology, reproductive medicine and oncology? How does a GP decide between the specialist gynaecologist or a subspecialist?

There seems to be remarkably little research into why and when an Australian GP chooses to refer a patient to a gynaecologist (specialised or subspecialised). One example of a study concerning gynaecological cancer referrals comes from BEACH (Bettering the Evaluation and Care of Health) data analysis from April 1998 to March 2006.1

The analysis looking at gynaecological cancer attendances in general practice in Australia demonstrated that this is an uncommon reason for attendance at a GP, constituting one in 1000 encounters with female patients. Referrals that were designated as being for gynaecological cancer were directed to gynaecologists (specialists) at a rate of 33 per 100 problems. 3.5 per 100 were directed to subspecialist oncologists and 1.5 per 100 to surgeons. The average referral pattern for BEACH is 8.2 per 100 problems. It should also be noted that BEACH only records new referrals, so some patients would have been referred at earlier encounters for the investigation and management of these issues.

This would have me conclude that, even for an area of highly specialised gynaecological problem, in the first instance, GPs are referring their patients to the gynaecologist of their own personal choice rather than being driven by subspecialisation.

So how do urban GPs, who have ready access to a large database of highly-skilled, competent specialists make decisions concerning the referral of the gynaecological problems of their patients?

I conducted a verbal poll of some of my local urban GPs as to what drives ongoing referrals to specialist gynaecologists versus subspecialist gynaecologists. Twelve out of 15 respondents to this informal gathering of information identified an obvious but frequently overlooked response of most GPs: they respond to good communication from both the specialist and the subspecialist. GPs will refer if they are confident of receiving good letters, feedback that is prompt and personal contact if necessary, whether by phone or email.

This confirms my own personal criterion when selecting a specialist for my patient. Overall, there are nine criteria that guide my decision-making, five of them concerning the communication I can expect or anticipate from the specialist:

- Timely and relevant information back to the GP regarding the specialist opinion following any consultation, investigation or intervention. This includes information regarding urgent need for hospitalisation or referral on to another specialist for a second opinion.

- Interactions with the front desk staff/receptionist! This includes both the GP interaction with the frontline phone service and the patient’s experience with appointment-making and attendances at the rooms. ‘Bulldog’ receptionists tend to put off referrers as well as patients.

It can be worthwhile trying to access your practice as an outsider to sample an experience! - Willingness to communicate with the GP over the phone regarding potential referrals, difficulties with management of current patients under care and/or information about how to manage a patient who may or may not actually need to be referred.

- Willingness to educate the referrer regarding management of gynaecological problems. Education can occur through detailed letters back to the referrer, but it should be noted that attending GP continuing professional development meetings at the local divisions/networks is an excellent way of both getting to know the GPs personally and demonstrating your personal skills and interests.

- Internet technologies and computerised files. Although this has not historically featured highly on the list of preferred communication criteria, it should be noted that GPs’ patient data management is becoming increasingly computerised. This means that specialists who start to communicate with data files and emails which can be downloaded into patient files (once the issue of embedded secure data is sorted out) will have a ‘head start’ in winning potential ongoing referrals. Certainly, having good technology helps ensure rapid and smooth communication.

The other criteria, which help in directing referrals, are:

- Alignment of the patient problem with the gynaecologist’s interests and skills. This may or may not mean referring to a subspecialist, but is the only criteria that influences my referral toward the specific skills of the practitioner.

- Access to services – timeliness and ability for patients that require urgent or semi-urgent attention to be ‘fitted in’.

- Practice geographic catchment zone. Where the consulting rooms are located, ease of access to the rooms, public transport accessibility, and public and private hospital access.

- Patient demographics, expectations and ability to pay. Bulk billing access when required or access to a flexible method of payment, access to public lists. The patient’s personal preference!

Certainly, patient expectations are a strong driving force behind referrals. A study done in London in between 1989 and 1990 by S Webb and M Lloyd looked at 1080 general practice consultations in 12 urban practices. Ten per cent of patients seen were referred on for specialist opinions. Twelve per cent of patients were expecting a referral prior to the consultation. Data analysis stated that if the patient came expecting a referral, they were six times more likely to be referred than otherwise.2

However, it would seem that the GP/gynaecologist communication really matters and GPs will make preferences based on their previous experiences of earlier referrals.

Catherine O’Donnell in Family Practice, December 2003, performed a literature review around GP referrals. She identified that GP referral patterns vary according to four basic parameters3:

- Patient characteristics

- Practice characteristics

- GP characteristics

- Access to the specialist

Her review also identified that GP referral rate variations could not and did not predict appropriateness or otherwise of the referral. Interestingly, she did not make comment about the importance or otherwise of communication. Perhaps the results of this study reflect the pre-existence of communication patterns between the GP referrer and the specialists, which were taken for granted by the researchers.

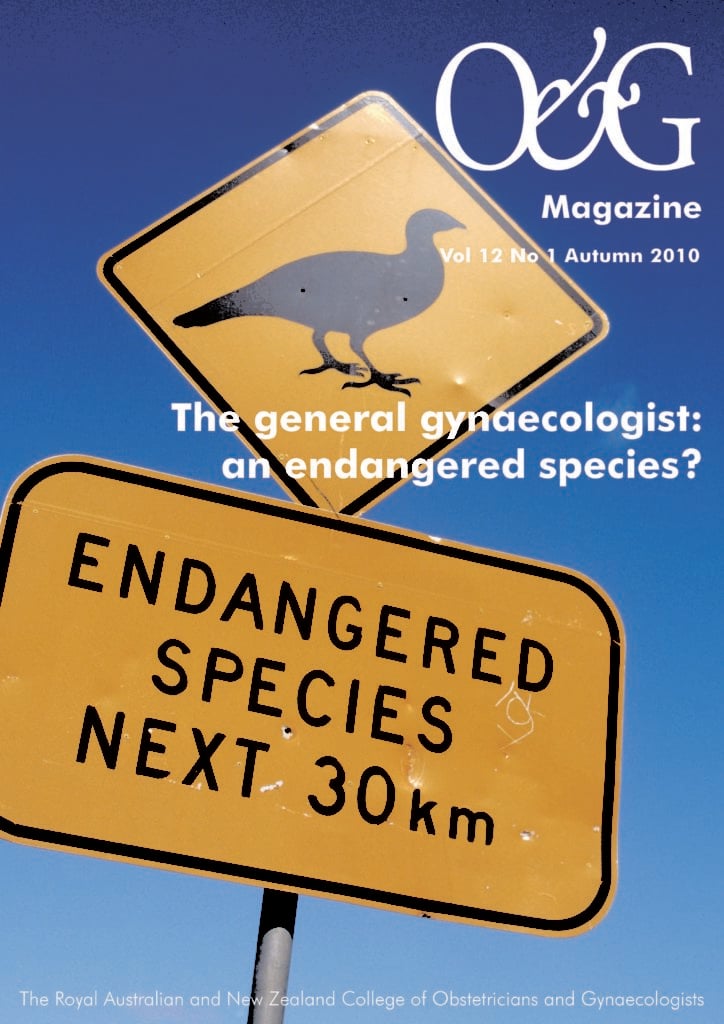

In conclusion, the important criterion driving GP referrals does not seem to be related to the subspecialisation of the gynaecologist. Instead, it is driven by the communications that occur alongside the referral – before, during and after the consultation. The general gynaecologist is certainly not an endangered species for the urban GP while these criterion keep being met!

References

- Bayram C, Pan Y, Miller G. Gynaecological cancer in Australian general practice. Australian Family Physician Vol 36 No 3; March 2007.

- Webb S, Lloyd M. Prescribing and referral in general practice: a study of patients’ expectations and doctors actions. Br J Gen Pract. 1994; April 44(381): 165-169.

- O’Donnell C A. Variation in GP referral rates: what can we learn from the literature? J Fam. Pract. 2000; 17: 462-471.

Leave a Reply