The natural history of a medical specialty can take many different paths. Technological advances can create a specialty with no equivalent in the past or, through sweeping cure, make a task redundant overnight. There were no radiologists before x-rays and no longer are doctors required to treat smallpox. More commonly, a specialty emerges as knowledge and techniques become beyond the scope of the generalist. Especially in large centres, the generalist relinquishes more and more of their practice as their more specialised colleagues take the lion’s share of the patient pool. If there is a procedural skill defining the specialty, then the process accelerates with the ‘generalist’ seemingly defined by default as one who has not ‘specialised’.

Within gynaecology there is still a strong representation of gynaecologists with a wide breadth of practice, but one only has to look at the physicians for one possible view of the future. In my own State, there are cardiologists and gastroenterologists, but general physicians are much thinner on the ground. Should the medical profession and the patients we serve be throwing bouquets or brickbats for these changes? A subspecialist, or a general O and G specialist with an interest in a subspecialty area, may ask if we wouldn’t prefer our pelvic floor surgery be done by someone doing 150 a year rather than 20, while a general O and G specialist might ask if it is necessary for us to visit a subspecialist for surgery that they may have performed many times in their own career? While both are reasonable sentiments, a cynic might also ask if the subspecialist is not partially motivated by prestige and the general O and G specialist by the loss of the satisfaction they gained from treating their patients across the spectrum of their health. A trainee like myself may lament the loss of exposure to the breadth of our specialty, as more surgery becomes the province of subspecialty fellows rather than the general O and G trainee. A rural specialist may find the argument academic, with access to subspecialists being practically difficult in many regional and rural centres.

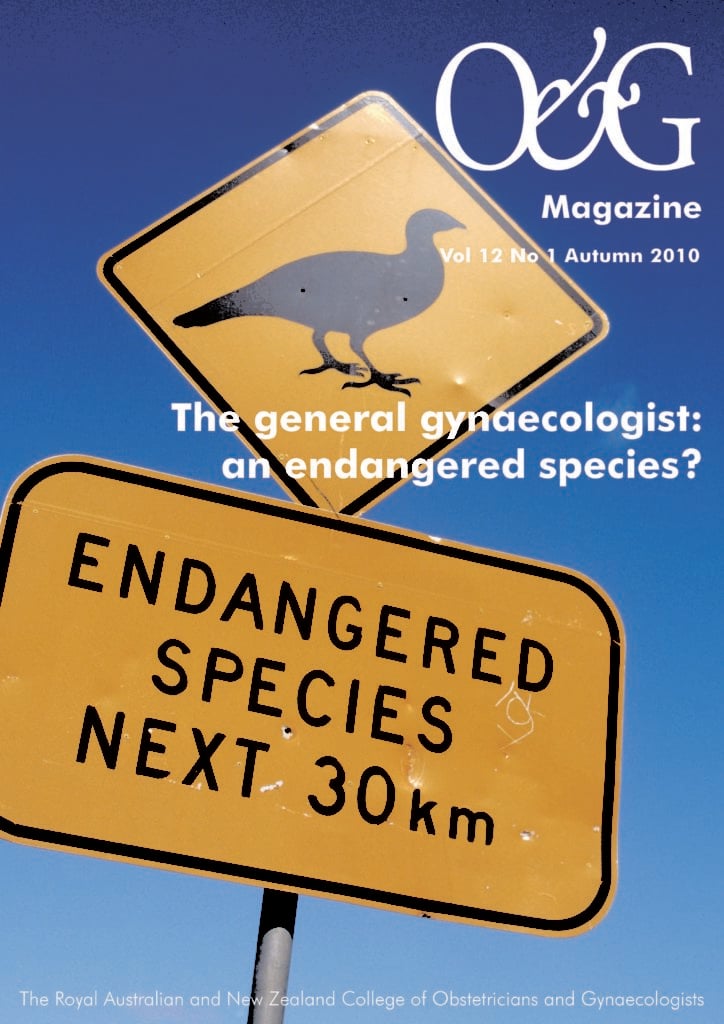

This issue of O&G Magazine asks the question: ‘Is the general gynaecologist an endangered species?’ If indeed we are endangered, we will not become extinct by the surgeons taking the care of women from us. Rather, it will be the division of gynaecology into ever more subspecialties and the reservation of techniques and operations by each of them. Colposcopy, mesh implants for prolapse and laparoscopic surgery all have subspecialties and societies lobbying for increased credentialing and training in their use. One can’t deny that subspecialties provide highly-skilled practitioners and that complex problems are best managed by those of us with the finest training and experience.

Unfortunately, neither Australia nor New Zealand has a perfect health system and there is not a gynaecological oncologist or a urogynaecologist on every corner, or even in every city. Many women, by necessity or choice, are treated primarily by a general specialist gynaecologist. It is these women and the doctors who care for them who will be most disadvantaged if non-subspecialist gynaecology practice becomes extinct.

As a nascent general O and G specialist, I would be disappointed if my care of women was restricted beyond the limits already imposed by our ethical and professional responsibility to practise within our training and expertise. There is no right answer to this question, but there is no question that gynaecology will decline as a specialty if we let it. We must be careful that the desire to increase our professionalism and expertise in ever more specific areas of practice, does not have the unintended result of limiting the ability of gynaecologists to continue to provide a comprehensive range of care to the women they serve.

Leave a Reply