Preterm delivery is a leading cause of neonatal mortality and morbidity, with cervical incompetence being one of many multifactoral causes.

Preterm delivery or recurrent pregnancy loss come with feelings of loss, frustration and failure for the woman and her physician. With improving technology and escalating expectation, delivery of a non-viable fetus is now delivery of a fetus at the limits of viability with attendant neonatal mortality and morbidity. Cervical incompetence is viewed in the wider context of preterm delivery and associated financial, social, emotional and medico-legal implications.

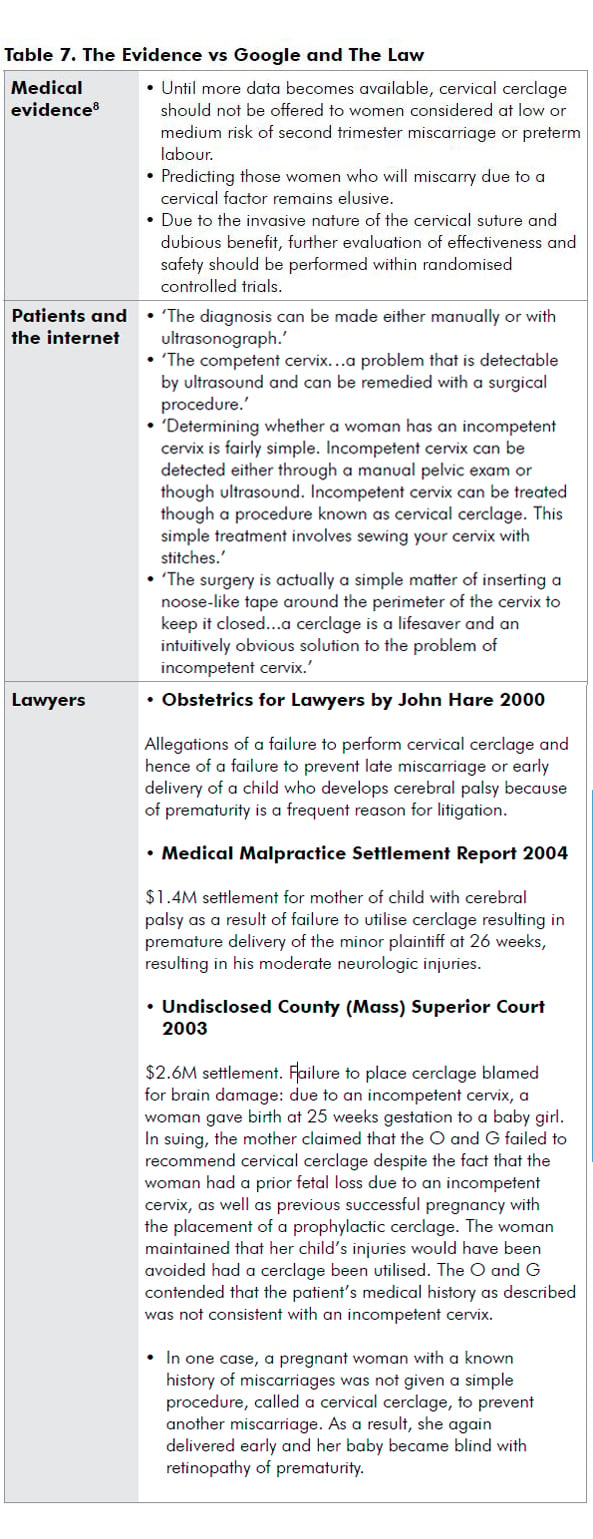

Cervical incompetence still has no clear definition, no proven objective diagnostic test or criteria, and in this evidence-based world, no evidence supporting its treatment. Lack of clarity potentially leads to confusion in standard of care and increased medico-legal dispute.1

Milestones

1658 Practice of Physick Cole, Culpepper and Rowland:

‘Slack orifice of the womb’

1865 Lancet – Gream – cervical incompetence

1955 VN Shirodkar and the Shirodkar suture (Mumbai)

1957 Ian McDonald and McDonald suture (Melbourne)

1965 Transabdominal sutures

1979 Transabdominal ultrasound scanning to detect cervical

dilatation

1986 Transvaginal ultrasound scanning and the short cervix 1997 Laparoscopic sutures

Changing definitions

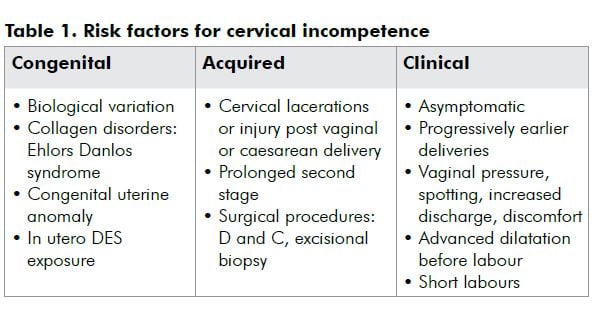

Traditional definitions are an expression of an anatomically defective cervix, congenital or acquired, with consequent recurrent second trimester loss or early preterm delivery. Ultrasound has changed the traditional view of the cervix being competent or incompetent, to degrees of incompetence. Cervical incompetence is considered a continuous variable, with various degrees leading to preterm delivery at different gestational ages.2,3

The diagnosis

Diagnosis is difficult as there is no diagnostic test prior to, during or after pregnancy. All proposed tests are inaccurate, inconvenient and have not been proven to predict outcome. Diagnosis is often based retrospectively on history and exclusion of other causes of preterm delivery. Typical history is of recurrent midtrimester spontaneous loss or early preterm delivery. Presentation is of cervical effacement and dilatation in the absence of uterine contractions; symptoms of pressure; protruding membranes or rupture of membranes; little bleeding; and a rapid delivery.

Ultrasound, the short cervix and cervical incompetence

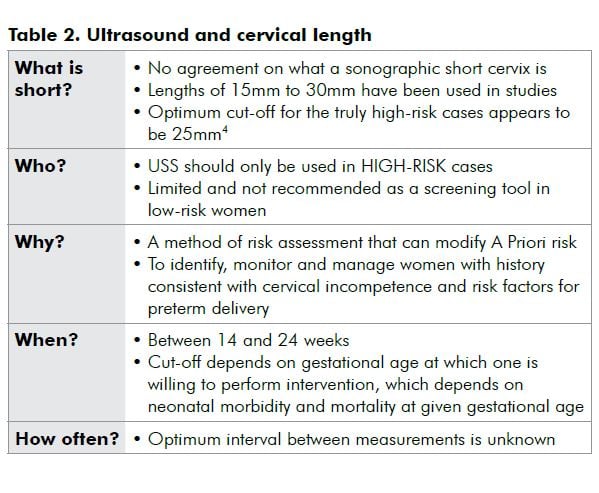

Ultrasound assessment of the cervix has been used since 1979. Transvaginal ultrasound scanning (USS), with closer proximity to the cervix and less cervical distortion from transducer pressure or a full bladder, is objective, highly reproducible and a reliable method to assess cervical length.

The short cervix is an expression of a spectrum of cervical disease or function. Other ultrasound parameters of funnelling and canal dilatation have not been verified.3

Cervical length and preterm delivery are inversely related: the shorter the cervix, the higher the risk of preterm delivery.4,5 Unfortunately, a short cervical length on USS has become synonymous with cervical incompetence.

- Risk factors for preterm delivery DO NOT mean risk factors for cervical incompetence.

- The short cervix is the final common pathway of multiple causes of preterm delivery.

- Any woman threatening spontaneous preterm delivery will develop a short cervix. Most will not be due to cervical incompetence. Fifty per cent of women with a cervix 15mm or less deliver after 32 weeks.2,4,5

- The majority of women considered high-risk for preterm delivery due to cervical incompetence do not develop a short cervix and do not need cerclage.

The treatment: cerclage

The many past and future interventions include:

- Cervical cerclage;

- Progesterone;

- COX2 selective non-steroidal anti-inflammatory agents;

- Anti-chemokine agents;

- Collagen injections;

- Vaginal pessary or inflatable balloons; and

- No sex, no excessive activity and bed rest.

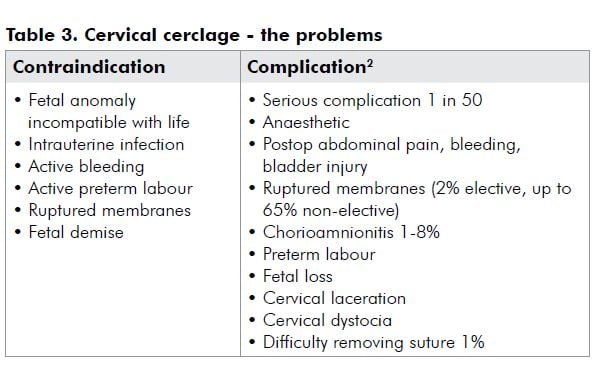

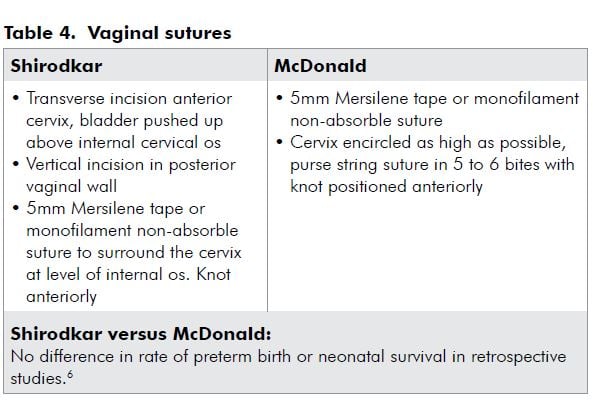

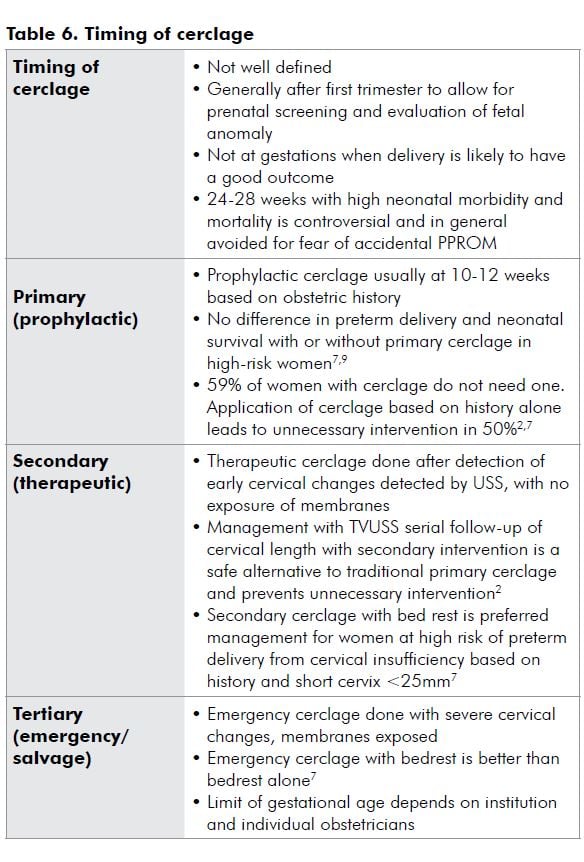

Cervical cerclage is traditionally offered on the basis of suspected cervical insufficiency based on obstetric history. The rationale being to provide mechanical support to the cervix, to prevent shortening and dilatation, and to prevent or postpone preterm delivery. Fifty years after the introduction of cervical cerclage, debates and controversy continue as to when and how cerclage should be used.

Approaches

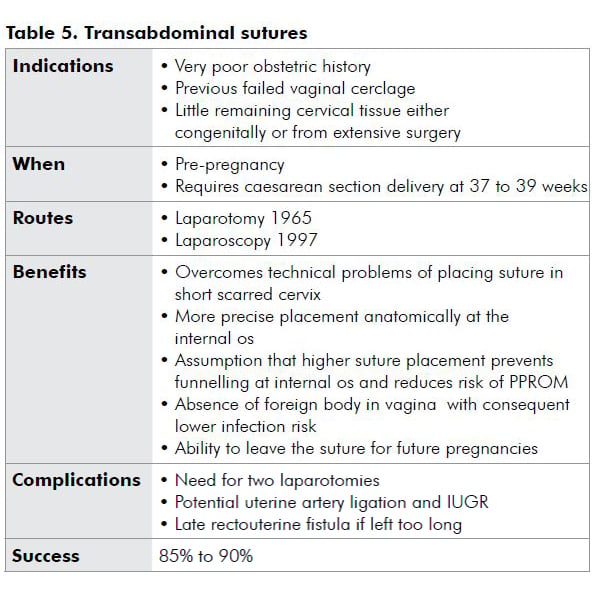

Evidence

Cerclage does appear to mechanically support the cervix and prevent shortening and dilatation.7 However, evidence is conflicting as studies vary in design, population, definitions and cervical length, precipitating intervention. The Cochrane Review has found no conclusive evidence that cervical cerclage in women perceived to be at risk of preterm delivery or second trimester loss attributable to cervical factors reduces the risk of pregnancy loss, preterm delivery or associated morbidity.8

Perspectives

Medicine is changing. Now, more than before, our practice is challenged by technology savvy, internet-surfing patients and their lawyers.

Summary

- Assess risk factors and take an obstetric history to identify women at risk of preterm delivery.

- It is difficult to identify who, among women at risk of preterm delivery, will have cervical incompetence.

- Prophylactic cerclage, based on history alone, is unneccesary intervention in 50 per cent of cases.

- Transvaginal USS is useful for high-risk women: Identifies the truly high-risk among the perceived high-risk cases.

- Transvaginal USS modifies A Priori risk. It can be used to avoid unnecessary intervention.

- Cervical length of less than or equal to 25mm is the optimum cut-off for identifying the high-risk cases.

- Transvaginal USS from 14 to at least 24 weeks, optimum interval unknown.

- Secondary cerclage if high-risk and short cervix on USS.

- Evidence does not suggest cerclage for a short cervix alone has any benefit.10 USS is not useful in low-risk women.

- A short cervix increases risk of preterm delivery but does not by itself equate to cervical incompetence.

References

- Romero R, Espinoza J, Erez O, Hassan S. The role of cervical cerclage in obstetric practice: Can the patient who could benefit from this procedure be identified? Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2006; 194:1-9.

- Althiosius S, Dekker G. Controversies regarding cervical incompetence, short cervix and the need for cerclage. Clinics in Perinatology 2004; 31:695-720.

- Vidaeff A, Ramin S. From Concept to Practice: The recent history of preterm delivery prevention. Part I: Cervical Competence. American Journal Of Perinatology 2006; 23:3-13.

- Althuisius S. The short and funnelling cervix: When to use cerclage? Curr Opin Obstet Gynecol. 2005; 17:574-578.

- Althuisius S, Dekker G. A five century evolution of cervical incompetence as a clinical entity. Current Pharmaceutical Design 2005; 11:687-697.

- Simcox R, Shennan A. Cervical Cerclage in the prevention of preterm birth. Best Practice & Research Clinical Obstetrics and Gynecology 2007; 21:831-842.

- Althuisius S, Dekker G, Geijn Hv, Bekedam D, Hummel P. Cervical incompetence prevention randomized cerclage trial (CIPRACT): Study, design and preliminary results. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2000; 166:896-900.

- Drakeley A, Roberts D, Alfirevic Z. Cervical cerclage for preventing pregnancy loss in women (Review). The Cochrane Collaboration 2009.

- Groom K, Bennett P, Golara M. Elective cervical cerclage versus serial ultrasound surveillance of cervical length in a population at high risk for preterm delivery. Eur J Obstet Gynecol Reprod Biol. 2004; 112:158-161.

- Belej-Rak T, Okun N, Windrim R, Ross S, Hannah M. Effectiveness of cervical cerclage for a sonographically shortened cervix: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2003; 189:1679-1687.

Leave a Reply