The Western Province of Papua New Guinea is a very underdeveloped part of the country. I live here with my wife and three children and we have been working here at Rumginae Rural Hospital on and off for about ten years now. It is a basic hospital with very simple facilities treating patients referred from a very large area and training community health workers to be the front-line in the delivery of healthcare to the rural areas of PNG.

My research tells me that PNG has one doctor for every 22,000 people, compared to one doctor per 377 people in Australia. I have just returned home from the ‘delivery suite’ after a very sad and unusual experience…

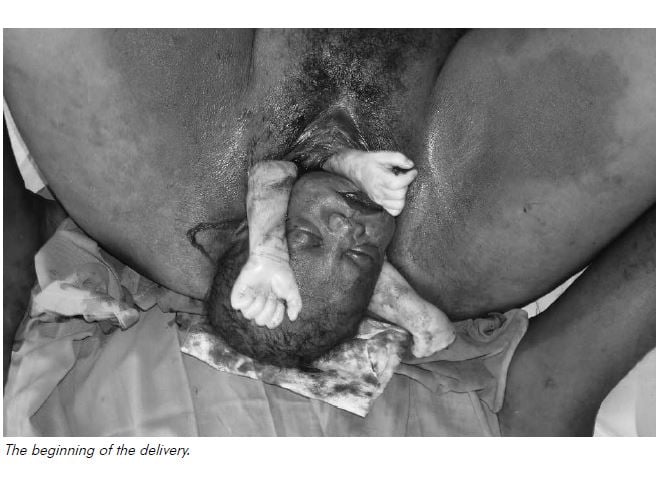

We had a woman arrive in the early hours of the morning in labour with twins. As she was making no progress, I was called to assist. The vacuum was already being set up by a nursing officer as I arrived. With vacuum, the descent seemed to be too slow but we did deliver a head, which then retracted back a bit. I started going through shoulder dystocia moves in my head and took over the delivery. We got her feet up around her ears and there was already a big episiotomy. I couldn’t deliver an anterior or a posterior shoulder despite help pushing from above the pubis to dislodge a shoulder. The torso just wouldn’t rotate to allow the posterior shoulder to deliver anteriorly – it just wouldn’t budge. Unfortunately, the nursing staff had started the vacuum despite not being able to get a catheter in…and I just couldn’t get one in which made symphysiotomy too dangerous, even if it could be done that quickly. I brought an arm down, then another, but decided that this arm did not belong to this fetus and fairly soon we had three arms down! Even this didn’t allow delivery. I tried to break a clavicle in desperation but still we made no progress.

By now it was close to five minutes and the baby had stopped opening its eyes to look at me. I tried lots of traction from the axilla, but still nothing (except a broken humerus). There was no way it was going back in either. I was stuck. We were getting well past five minutes now so I had a look with our small ultrasound to see if the other baby was alive. It didn’t make sense how I could have BOTH shoulders free, but the baby not coming. Interlocking twins head and pelvis shouldn’t occur. I was getting suspicious of something else.

The scan was odd. I’m no sonographer and I found it hard to distinguish the spinal cord of one baby from the other and to find the heart. The head of ‘twin two’ was not in any position to be obstructing the delivery of ‘twin one’. Where I was sure the heart of twin two was, nothing was moving. I looked for a while and became convinced it was what it turned out to be. I was getting prepared (more mentally than any physical preparation) for a destructive delivery but wanted to try one more time.

Now I was sure that both babies were dead, I pulled with a lot more force and delivered vaginally conjoined twins – two heads, four arms, four legs and joined at the chest and the abdomen! Apart from the episiotomy, there were no tears, but the poor woman had a retained placenta which I removed in the delivery suite.

I would have liked to have known beforehand and planned a caesarean section, but maybe the size of the caesar cut would have made me want to tell her never to have any more children and tie her tubes. Also, a caesarian in our underequipped, understaffed setting is not without its dangers. I suppose, this way, she can deliver normally next time. Siamese twins would have an appalling survival rate here in PNG if we had been able to deliver them alive.

It is a sad story, but it has to be seen in contrast with any gains in maternal and child healthcare. I have been privileged to serve here in PNG, training national health workers in all areas of medicine during their two-year community health worker training program. By being here, I have also been able to help women in difficulty through simply overseeing their management; teaching and using a ventouse; performing caesarians (or rarely symphysiotomy); resuscitating babies; as well as teaching and demonstrating the repairing of tears and episiotomies. We try also to be involved in a small way in tackling demographic entrapment through family planning training, awareness and services. Then there are the many non-obstetric patients, but that is another story altogether. Papua New Guinea is our nearest neighbour. Please spare a thought and a prayer for these neighbours living in difficult conditions.

Leave a Reply