Timor Leste is the world’s newest nation and despite having huge oil and gas reserves, it is also one of the world’s poorest nations.

After 25 years of occupation, followed by a bitter fight for independence, Timor Leste has very depleted infrastructure in all areas of government. This, in conjunction with a high birth rate, has resulted in high rates of maternal, neonatal and infant mortality.

At the end of 2005, the Rotary Australia World Community Service entered into a Memorandum of Understanding with the Timor Leste Ministry of Health, to assist the public sector health system provide better services for safe motherhood in Bobonaro district, Timor Leste. This Safe Motherhood Project is part of an Infancy, Midwifery, Obstetrics and Gynaecology (IMOG) program and is coordinated by the Rotary Club of Morialta, South Australia. The project is funded by Rotarian and non-Rotarian philanthropists and organisations, with technical support provided by specialists from the Discipline of Public Health, the University of Adelaide and the Royal Australian and New Zealand College of Obstetricians and Gynaecologists (RANZCOG). Many O and Gs and other medical specialists provide voluntary service as part of this project.

The focus is on safe motherhood because the maternal and infant mortality rates of Timor Leste are among the highest in the world. The high total fertility rate of 7.7 is contributing to the high maternal mortality.3 While about 43 per cent of pregnant women receive care from skilled healthcare providers, only about 14 per cent of women access antenatal care according to the recommended schedule. The project is based in the Bobonaro District which has a population of approximately 85,000. A large number of people live in small villages. Public transport is not available to many people in the rural and remote communities. The terrain is rough and hilly and often becomes impassable during the wet season.

The goal of the project is to improve maternal and child health. The project aims to achieve this goal through strengthening antenatal care; birthing; postnatal care; emergency obstetric care; human resource development; referral systems; planning and management; and infrastructure development. This is in line with the strategies recommended for safe motherhood, therefore, access to skilled birth attendants, quality obstetric care and access to contraception to avoid unintended pregnancies.5 Community outreach for public health interventions, community involvement and improved utilisation of public sector health services are some of the project’s strategies.

We all know that delay in access to appropriate obstetric care is a major cause of deaths in women during pregnancy and delivery. The three phases of delay include:

- Delays due to lack of a prompt decision to seek care for women

- Delays in reaching an adequately equipped healthcare facility

- Delays in provision of effective care even after arrival at the facility.2

We noted that all three types of delays are contributing to maternal mortality in the Bobonaro district. Therefore, the project in Bobonaro is assisting the government health system by:

1. Removing the delays due to lack of decisions to seek care

We are assisting government staff in reaching out to the community to improve the understanding about the need for appropriate obstetric care. The project has provided eight motorbikes to the midwives and nurses stationed at the community health centres and health posts. The midwives are encouraged to: reach out and provide antenatal care; identify high-risk pregnancies; motivate women and their families to seek care provided by an appropriately trained midwife or doctor; and provide the community with information about how to contact a hospital and call for an ambulance.

2. Removing the delays due to lack of transport

Our project has provided an ambulance to the government health system, including ongoing funds for fuel, maintenance and a driver. Our team helped government staff to develop a log which provides information on the use of the ambulance and helps in planning better access for women in rural and remote areas. A midwife accompanies the ambulance driver for all obstetric emergencies. In the past, there was only one ambulance in the whole district, which at times was non functional due to lack of funds. The addition of an ambulance and the resources to keep it operating are a great asset. The driver, midwives and other associated healthcare staff feel privileged to be in a situation where they contribute to saving the lives of women suffering from pregnancy and delivery complications. This year, additional training for the ambulance staff was conducted by a visiting volunteer obstetrician and the need for supplies for the ambulance was reassessed.

3. Removing the delays due to lack of quality care at the health facilities

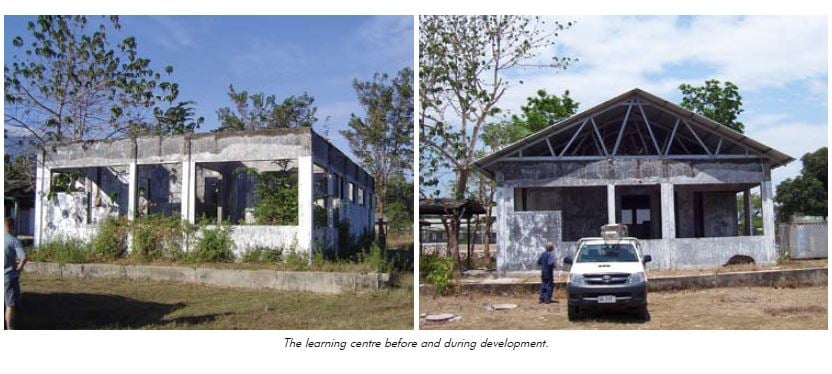

We are supporting government plans for upgrading community health centres (CHCs), health posts and the Bobonaro District Hospital. Visiting obstetricians and medical laboratory specialists have provided training to doctors, midwives and laboratory technicians. A building in the hospital premises, that was burnt during the independence struggle, has been re-built and converted into a learning centre by the project volunteers. There are six CHCs and 15 health posts in the Government health system Bobonaro district. However, at present, no deliveries are conducted at these centres and posts, nor are they equipped to provide safe emergency obstetric care. Building materials, construction equipment and supplies have been procured and plans are underway for the renovation and construction of consulting rooms and delivery suites at the two CHCs in Cailaco and Atabae. As a consequence, these centres will be able to provide emergency obstetric care. This upgrade is to start in March 2009. Such developments provide the additional benefits of contributing to the local economy, as considerable sums of money are spent to purchase materials and temporary jobs are created as well. The staff at CHCs, including nurses and midwives, are highly motivated. They need adequate facilities, equipment and some additional training to make optimum use of the upgraded facilities. The list of equipment and medicine needed is prepared in line with what is recommended for basic emergency obstetric care. These requirements can easily be met at low cost once the facilities are upgraded and staff have the additional training.

Health is a fundamental human right and governments have a responsibility to make sure that people have easy access to quality care. With a philosophy that overseas aid should contribute to the sustainable development of local systems and considering the vital role of governments, we think it is essential to work together with the Timor Leste Government. For these reasons, we have refrained from initiating separate and parallel services in Bobonaro.

We understand that removing the delays in accessing the obstetric care is not sufficient by itself. The recommended strategies for reducing maternal mortality include access to skilled birth attendants and quality obstetric care; access to contraception to prevent unintended pregnancies; and measures to address other health and reproductive health issues6 such as high prevalence of malaria; anaemia; infections; malnutrition; reproductive tract infections; and sexually transmitted infections. Therefore, the project team, including midwives and public health professionals, will be working with the community and government healthcare staff to improve outreach services, provision of health education, vaccinations, contraceptives, malaria bed nets and nutritional supplements.

Working on these tasks is not without challenges. There are very few local trained midwives and doctors in Timor Leste. Identifying locals to work on projects like ours is difficult. Volunteers from Australia are generally only available to work overseas for a short period of time and that makes it difficult to forge effective working relationships in the local setting. To some extent, language barriers affect the capacity of volunteers to provide support. Occasional internal conflicts in Timor Leste and the associated violence and displacement of people have also affected the health services development efforts. Those post-conflict challenges have been presented in some detail in a recent article by Marlowe and Mahmood (2009) in the Asia Pacific Journal of Public Health.1 The project has contributed to our learning about the challenges and allowed us to gain knowledge on how to overcome those challenges. We intend to use these learning experiences to continue input in Timor Leste and in other developing communities.

References

- Marlowe PL, Mahmood MA. Public health and health services development in post-conflict communities: a case study of a safe motherhood project in East Timor. Asia Pacific Journal of Public Health 2009. In press.

- Thaddeus S, Maine D. Too far to walk: maternal mortality in context. Soc Sci Med. 1994; 38:1091-1110.

- Timor-Leste Ministry of Health. National Strategy for Health Promotion 2004-2010. Dili: Ministry of Health; 2004.

- Timor-Leste Ministry of Health. National Reproductive Health Strategy. Dili: Ministry of Health; 2004.

- UNFPA. A thematic fund for maternal health: Accelerating Progress Towards Millennium Development Goal 5: No Women Should Die Giving Life. UNFPA 2006.

- Liljestrand J. Strategies to reduce maternal mortality worldwide. Current Opinions in Obstetrics & Gynaecology 2000; 12(6) 513-517.

Leave a Reply