More than three million babies are stillborn across the world each year.1 Although the majority of these losses occur in developing nations, stillbirth remains a common adverse outcome in countries such as Australia and New Zealand, where the incidence is about one in 200.2

Careful investigation to determine the causes of a stillbirth is important as knowledge of the aetiology allows informed counselling about risks faced in a subsequent pregnancy and planning of management strategies.2,3,4

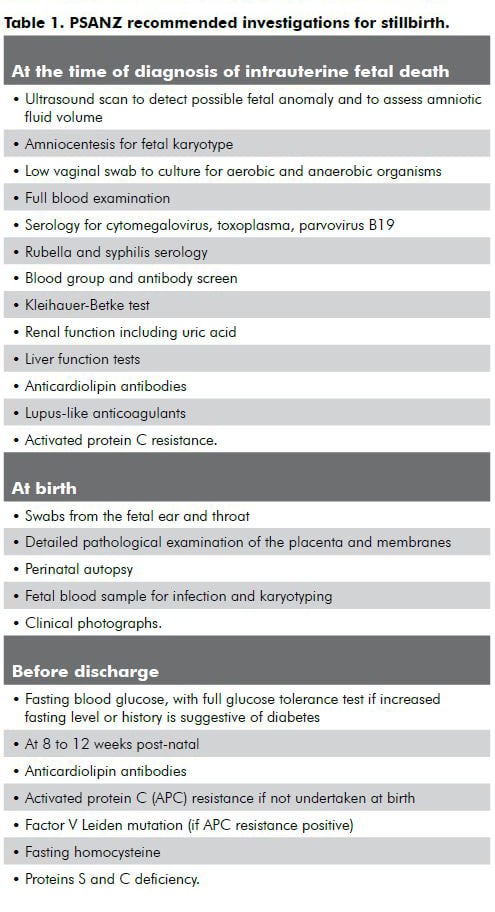

Unfortunately, no cause for a stillbirth can be found in as many as one-third of cases.2 This situation is usually referred to as ‘unexplained’ stillbirth. There are many coding systems used to classify causes of perinatal death and stillbirths should only be deemed ‘unexplained’ if complete investigation fails to yield a cause. The Perinatal Society of Australia and New Zealand (PSANZ) has recommended a set of investigations for stillbirth (see Table 1). Regrettably, for various reasons, investigation is incomplete for many fetal deaths and the term

‘unexplored’ stillbirth is probably more appropriate.5

Unexplained stillbirth is an enigma. Numerous population-based studies have defined risk factors for this condition (see Table 2), yet extensive research efforts over two decades have not led to any reduction in the incidence of this disastrous outcome.2,6 Most of the published literature is concerned with population-based strategies for primary prevention of unexplained stillbirth. Unfortunately, many of the risk factors are not easily amenable to modification – lower socio-economic status, maternal age and race for example. Other risks such as maternal obesity, smoking and diabetes are routinely addressed during antenatal care anyway. Since the rate of stillbirth is not decreasing, the commonest issue facing providers of antenatal care is what to offer women in their next pregnancy.

What happens in the next pregnancy after unexplained stillbirth?

Overall, the odds ratio for recurrence of stillbirths from all causes is almost five7, but studies of pregnancy outcomes subsequent to unexplained stillbirth have not reported any significant increase in the adjusted risk of perinatal death compared to women who have not suffered a stillbirth.8,9,10,11 This should be reassuring news for women. However, those studies did find that pregnancy after stillbirth is characterised by increased rates of induced labour, elective and emergency caesarean section, preterm birth and low birthweight. This may be an example of a phenomenon known as the Hawthorne Effect: when a severe adverse outcome (such as stillbirth) occurs, clinicians will be exceptionally cautious in the next pregnancy, usually maintaining intense surveillance and a low threshold to intervene. Thus, the management in the next pregnancy is fundamentally different and cannot be easily compared with what happened first time around.

Our own study of women who have suffered an unexplained stillbirth found that they want high levels of surveillance and early delivery in their next pregnancy.12 Both women and obstetricians seem to want the same pattern of care in the next pregnancy. It is not surprising that Australian data show that rates of induced labour and elective caesarean section are increased in this setting suggesting a strong Hawthorne Effect.9 Although early delivery would be expected to reduce the rate of stillbirth at a population level, it increases the potential for iatrogenic complications such as prematurity, failed induction, instrumental delivery, emergency caesarean section and post-partum haemorrhage. While these are undoubtedly preferable to stillbirth, they are still adverse outcomes.

Pre-pregnancy

It is common for women and their partners to try for another pregnancy soon after stillbirth. Older studies have found that almost half of such couples are pregnant within six months.13 For this reason, timely consultation with the couple before attempting pregnancy again is very important. Since many stillbirths classified as unexplained are actually incompletely investigated, it is important to carefully review results of all investigations and inform the couple where areas of uncertainty lie. A clinically useful way of looking at this is to describe stillbirths as unexplained but non-recurrent (where investigation was sufficiently complete to exclude aetiologies with a risk of recurrence), or unexplained but potentially recurrent (where the level of investigation makes it impossible to assign a prognosis).

In any case, before attempting pregnancy again, maternal conditions increasing the risk of stillbirth recurrence should be sought: hypertension, thyroid and chronic renal disease, diabetes, thrombophilias, lupus, blood group antibodies and hyperhomocysteinaemia. If found, attempts can be made to stabilise the conditions before the next pregnancy. Rarely chronic infectious conditions associated with stillbirth are diagnosed, the commonest being toxoplasmosis, syphilis and possibly chlamydia.14 There is some evidence from animal models that periodontal anaerobes might cause stillbirth, so dental review is advisable.15 Women at social disadvantage can be offered additional social supports, but admittedly, evidence of the effectiveness of such interventions is equivocal.16 Obesity and smoking are important modifiable risk factors for adverse outcome in the next pregnancy.

It is worth noting that timing of the next pregnancy can play a role. Women who conceive within 12 months of a perinatal loss seem to have higher rates of depression and anxiety.17 These emotional states have the potential to influence pregnancy outcome since management of maternal anxiety and depression may reduce the risk of preterm birth and possibly other adverse pregnancy outcomes.18,19 Pathological grief responses can be difficult to pick, so formal assessment of the couples using instruments, such as the Edinburgh Postnatal Depression Scale20 and the Spielberger State-Trait Anxiety Inventory17, might identify those needing referral for further psychological assessment before pregnancy.

Management in early pregnancy

There are no data addressing the risks, if any, that women face in early pregnancy after an unexplained stillbirth. Notwithstanding, early ultrasound is important to accurately establish the gestational age. The most effective intervention for reducing the rate of stillbirth is likely to be timely delivery, once the fetus is mature, probably no later than 39 weeks gestation.2,21,22,23 Induction of labour is likely be offered in these pregnancies and adverse outcomes (emergency caesarean delivery, instrumental delivery and post-partum haemorrhage) are related to either attempted induction at an early gestation or in older age groups.24 Accurate determination of gestational age with ultrasound as early as possible reduces the risk of inadvertent premature delivery and failed induction.25

Abnormal fetal karyotype may have remained undiagnosed even with careful work-up at the time of a stillbirth. Failure of cell culture is common when there has been a delay between death and delivery. The commonest conditions associated with fetal death are trisomies 21, 18 and 13, and these may impart an empirical recurrence risk of between five and 15 per cent, depending on the age of the woman.26,27 Since invasive karyotyping increases the risk of pregnancy loss, care must be taken counselling younger women. Where a fetal karyotype could not be obtained from the stillbirth, young women should be offered risk estimation using combined first trimester screening with resort to invasive karyotyping as indicated by screening results.

Management in later pregnancy

Most women who have had an unexplained stillbirth will seek ‘increased fetal surveillance’ and ‘early delivery’ in subsequent pregnancy, although a desire for elective caesarean delivery is uncommon.12 Such a pattern of care is likely to be promoted by obstetricians as well.28 The methods of surveillance commonly undertaken are regular ultrasound, cardiotocography (CTG) and fetal movement surveillance.

Growth restriction seems to be a factor in many unexplained stillbirths29, with failure to identify growth restriction a common factor.30 Antenatal measurement of symphysio-fundal height, though almost universal, is of limited value in screening for growth restriction.31 For these reasons, it would seem prudent to offer regular fetal ultrasound for the detection of abnormal fetal growth because growth restriction is a final common pathway for many pathological processes. Uterine artery flow measurement by Doppler has been shown to be a useful predictor of stillbirth related to growth restriction up to 32 weeks gestation, but such testing is of limited value in later pregnancy.32

Use of ultrasound-based fetal weight estimates can be falsely reassuring.33 The use of customised centile charts has been found to be a better predictor of fetal growth restriction and stillbirth. There is no evidence yet that prospective use of such charts reduces the rate of perinatal death in screened populations.34 A better screening tool in later pregnancy is umbilical artery Doppler study. Screening of high-risk populations using this method is the only strategy associated with a trend toward improvement in perinatal mortality.35 Unfortunately, the optimal frequency of such ultrasounds remains uncertain.

Regular CTG testing to establish ‘fetal wellbeing’ is very commonly practised, yet there is little evidence to support it. The only study of CTG surveillance in pregnancy after stillbirth showed no effect on perinatal mortality.36 Meta-analysis of studies of regular CTG testing in ‘high or intermediate risk’ pregnancies actually detected a paradoxical trend to increased perinatal deaths.37 On the basis of current evidence, routine CTG testing undertaken as a screening strategy, in the absence of specific clinical concerns such as reduced fetal movement, is unlikely to benefit women.

A time-honoured method of fetal surveillance is formal fetal movement charting, commonly aided by ‘kick charts’. This should be no surprise, since many cases of intrauterine fetal deaths are preceded by a decrease in fetal movements, often for up to a day beforehand. A wide variety of adverse pregnancy outcomes seem to be associated with reduced fetal movements.38 Unfortunately, the use of ‘kick charts’ in prospective studies have failed to demonstrate any effect on the rate of perinatal mortality.39 That study did however have a number of serious flaws. Reduction in fetal movements is a very common symptom, with as many as 15 per cent of pregnant women presenting with it.40 Although the conclusions of prospective trials of ‘kick charts’ have been challenged,41 there is still no convincing evidence that routine use of fetal movement charting improves pregnancy outcomes.40 While the jury is probably still out, it remains important to encourage women to report abnormal patterns of fetal movement early and to undertake assessment without delay.

Delivery

Women will very commonly request early delivery in pregnancies that follow unexplained stillbirth12 and data suggest that many obstetricians accede to such requests.28 The risk of stillbirth, using undelivered fetuses as a denominator, increases almost exponentially after 39 weeks gestation.42 Obviously, should surveillance detect adverse fetal status then management and timing of delivery must be individualised. The great majority of pregnancies after an unexplained stillbirth will be uncomplicated. Many authors concede that the single most important aspect of management of uncomplicated pregnancies after an unexplained stillbirth may be early delivery, perhaps by 39 weeks.3,4,6 When delivery is delayed beyond this gestation, prudence demands careful surveillance, probably with an ultrasound examination to estimate amniotic fluid volume and umbilical artery flow. Only a small number of women will request elective caesarean delivery in this setting, unless they have had a previous caesarean or were advised at the time of the stillbirth to have a caesarean birth in their next pregnancy.12

Research is needed

The few studies that guide management in pregnancies after unexplained stillbirth leave many questions unanswered and there is thus an urgent need for a large prospective study in this setting. Because unexplained stillbirth is a relatively uncommon outcome (there are about 2000 such losses each year in Australia), and because late fetal death is so traumatic, it is unlikely that randomised controlled trials of antenatal management will ever be undertaken.

Conclusion

Everyone involved in the care of a couple who have had an unexplained late fetal death find it distressing and challenging. Many couples will try to become pregnant again, and will seek guidance on the risks they face and whether anything can be done differently the next time. Careful surveillance and early delivery play an important role in optimising the outcome, although with the consequence that some adverse outcomes (low birthweight, preterm delivery, emergency caesarean section and post-partum haemorrhage) are likely to result from these interventions. It is critical that women and their families are provided with reassurance and support.

References

- Stanton C, Lawn J, Rahman H, Wilczynska-Ketende K, Hill K. Stillbirth rates: delivering estimates in 190 countries. Lancet 2006; 367: 1489-94.

- Fretts RC. Etiology and prevention of stillbirth. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2005; 193: 1923-35.

- Reddy UM. Prediction and prevention of recurrent stillbirth. Obstet Gynecol. 2007; 110: 1151-64.

- Silver RM. Fetal death. Obstet Gynecol. 2007; 109: 153-67.

- Measey MA, Charles A, d’Espaignet ET, Harrison C, Deklerk N, Douglass C. Aetiology of stillbirth: unexplored is not unexplained. Aust NZ J Public Health 2007; 31: 444-9.

- Smith GCS, Fretts RC. Stillbirth. Lancet 2007; 370: 1715-25.

- Sharma PP, Salihu HM, Oyelese Y, Ananth CV, Kirby RS. Is race a determinant of stillbirth recurrence? Obstet Gynecol. 2006; 107: 391-7.

- Heinonen S, Kirkinen P. Pregnancy outcome after previous stillbirth resulting from causes other than maternal conditions and fetal abnormalities. Birth 2000; 27: 33-7.

- Robson S, Chan A, Keane RJ, Luke CG. Subsequent birth outcomes after an unexplained stillbirth: preliminary population-based retrospective cohort study. Aust NZ J Obstet Gynaecol. 2001; 41: 29-34.

- Lurie S, Eldar I, Glezerman M, Sadan O. Pregnancy outcome after stillbirth. J Reprod Med. 2007; 52: 289-92.

- Black M, Shetty A, Bhattacharya S. Obstetric outcomes subsequent to intrauterine death in the first pregnancy. Br J Obstet Gynaecol. 2008; 115: 269-74.

- Robson SJ, Leader LR, Bennett MJ, Dear KGB. Do women’s perceptions of care at the time of unexplained stillbirth influence their wishes for management in subsequent pregnancy? An Internet based empirical study. J Obstet Gynaecol Res. In press.

- Forrest G, Standish E, Baum J. Support after perinatal death: a study of support and counselling after perinatal bereavement. BMJ 1982; 285: 1475-9.

- Baud D, Regan L, Greub G. Emerging role of Chlamydia and Chlamydia-like organisms in adverse pregnancy outcomes. Curr Opin Infect Dis. 2008; 21: 70-6.

- Boggess KA, Madianos PN, Preisser JS, Moise KJ, Offenbacker S. Chronic maternal and fetal Porphyromonas gingivalis exposure during pregnancy in rabbits. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2005; 192: 554-7.

- Hodnett ED, Fredericks S. Support during pregnancy for women at increased risk of low birthweight babies. Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews 2003; (3): CD000198.

- Hughes P, Turton P, Evans C. Stillbirth as a risk factor for depression and anxiety in the subsequent pregnancy: cohort study. BMJ 1999; 318: 1721-4.

- Littleton HL, Breitkopf CR, Berenson AB. Correlates of anxiety symptoms during pregnancy and association with perinatal outcomes: a meta analysis. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2007; 196: 424-32.

- Orr ST, Reiter JP, Blazer DG, James SA. Maternal prenatal pregnancy related anxiety and spontaneous preterm birth in Baltimore, Maryland. Psychosom Med. 2007; 69: 566-70.

- Cox JL, Holden JM, Sagovsky R. Detection of postnatal depression. Development of the 10-item Edinburgh Postnatal Depression Scale. Br J Psychiatry 1987; 150: 782-6.

- Smith GCS. Estimating risks for perinatal death. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2005; 192: 17-22.

- Cotzias C, Paterson-Brown S, Fisk N. Prospective risk of unexplained stillbirth in singleton pregnancies at term: population-based analysis. BMJ 1999; 319: 287-8.

- Fretts RC, Elkin EB, Myers ER, Heffner LJ. Should older women have antepartum testing to precent unexplained stillbirth? Obstet Gynecol. 2004; 104: 56-64.

- Glantz JC. Elective induction vs spontaneous labor. Associations and outcomes. J Reprod Med. 2005; 50: 235-40.

- Neilson JP. Ultrasound for fetal assessment in early pregnancy. Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews 1998; 4: CD000182.

- Warren JE, Silver RM. Genetics of pregnancy loss. Clin Obstet Gynecol. 2008; 51: 84-95.

- Lister T, Frota-Pessoa O. Recurrence risks for Down syndrome. Hum Genet. 1980; 55: 203-8.

- Robson S, Thompson J, Ellwood D. Obstetric management of the next pregnancy after an unexplained stillbirth: An anonymous postal survey of Australian obstetricians. Aust NZ J Obstet Gynaecol. 2006; 46: 278-81.

- Kady S, Gardosi J. Perinatal mortality and fetal growth restriction. Best Pract Res Clin Obstet Gynaecol. 2004; 18: 397-410.

- Saastad E, Vangen S, Frøen JF. Suboptimal care in stillbirths – a retrospective audit study. Acta Obstet Gynecol Scand. 2007; 86: 444-50.

- Neilson JP. Symphysis-fundal height measurement in pregnancy. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2004; (2): CD000944.

- Smith GC, Yu CK, Papageorghiou AT, Cacho AM, Nicolaides KH. Maternal uterine artery Doppler flow velocimetry and the risk of stillbirth. Obstet Gynecol. 2007; 109: 144-51.

- Dudley NJ. A systematic review of the ultrasound estimation of fetal weight. Ultrasound Obstet Gynecol. 2005; 25: 80-9.

- Clausson B, Gardosi J, Francis A, Cnattingius S. Perinatal outcome in SGA births defined by customised versus population-based birthweight standards. BJOG 2001; 108: 830-4.

- Haram K, Säfteland E, Bukowski R. Intrauterine growth restriction. Int J Gynaecol Obstet. 2006; 93: 5-12.

- Weeks J, Asrat T, Morgan M, Nagoette M, Thomas SJ, Freeman RK. Antepartum surveillance for a history of stillbirth: when to begin? Am J Obstet Gynecol. 1995; 172: 486-92.

- Pattison N, McCowan L. Cardiotocography for antepartum fetal assessment. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2000; 2: CD001068.

- Froen JF, Arnestad M, Frey K, Vege A, Saugstad OD, Stray-Pedersen B. Risk factors for sudden intrauterine unexplained death: epidemiologic characteristics of singleton cases in Oslo, Norway, 1986-1995. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2001; 184: 694-702.

- Grant A, Elbourne D, Valentin L, Alexander S. Routine formal fetal movement counting and risk of antepartum late death in normally formed singletons. Lancet 1989; 2 (8659): 345-9.

- Heazell AEP, Froen JF. Methods of fetal movement counting and the detection of fetal compromise. J Obstet Gynaecol. 2008; 28: 147-54.

- Frøen JF. (2004). A kick from within – fetal movement counting and the cancelled progress in antenatal care. J Perinatal Med. 2004; 32: 13-24.

- Yudkin P, Wood L, Redman C. Risk of unexplained stillbirth at different gestational ages. Lancet 1987; 1: 1192-4.

Leave a Reply