Systematic ascertainment of maternal deaths and the conduct of confidential enquiries into the circumstances and causation of the deaths are fundamental to the assessment of the safety of our maternity services.

This process started in England and Wales in 1952 and UK triennial reports have been published since 1985, with recommendations to the relevant professions about standards of care and practice changes needed to reduce the risk.1

Australia was not far behind, having FRANZCOG produced triennial reports on maternal deaths since 1964 and some work on selected morbidities has recently commenced. The latest national report addressed deaths in Australia during the triennium 2003-20052 but there is concern about the timeliness of these surveys. Even if the report for the next triennium (2006-2008) comes out in 2010 (which is by no means assured), it will be reporting on events which occurred three to five years previously, which may well diminish the relevance of any conclusions and recommendations.

In accordance with that used by the World Health Organisation (WHO), the definition used in Australia includes direct and indirect deaths only, within 42 days of the termination of pregnancy, although incidental deaths are also considered in most reports from individual States and Territories. Late deaths (up to 365 days) are reported by some jurisdictions. It is usually easy to classify a death as a direct or an indirect death (for example, a death from eclampsia in a previously healthy primigravida is unequivocally a direct death, and a death from Eisenmenger’s syndrome in a woman who has had corrective surgery for a congenital cardiac defect is unequivocally an indirect death). However, sometimes the distinction is harder to make. For example, is death from suicide, six months following pregnancy, a direct, indirect or incidental death? Currently in Australia, such a case would not be included in the national report because it occurred more than 42 days following the termination of the pregnancy. There is also increasing concern about excluding ‘incidental’ deaths from consideration because of this difficulty in making the judgement that a death during pregnancy was entirely unconnected with the pregnancy, and as the classification process involves individual judgement, there are inevitable inconsistencies between jurisdictions. For this reason alone, a strong argument can be made from a public health perspective, to have a national uniform approach to the consideration of all deaths in pregnancy and up to the end of the first year after the termination of the pregnancy.

The Australian national reports have used the same definitions since 1973. Over this 32-year period, in Australia, there has been a small increase in the number of births (approximately six per cent), but the number of reported maternal deaths has fallen from 92 to 65, a reduction of nearly 30 per cent. Compared to other parts of the world, the risk of maternal death in Australia is very low, about one death for every 10,000 women giving birth. The maternal mortality ratio (MMR) in Australia is 8.4 per 100,000; in Sub-Saharan Africa, it is 100 times greater, about one death for every 100 women giving birth.3

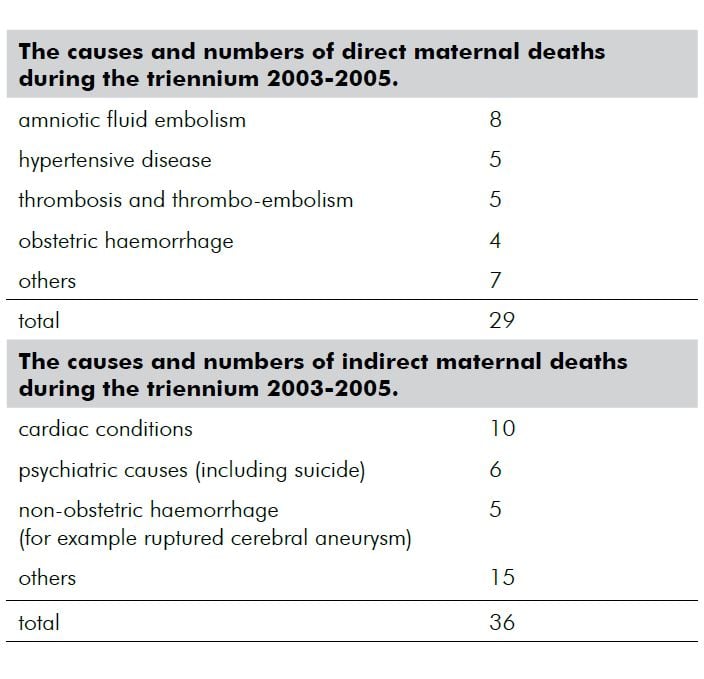

Note that psychiatric conditions are the second leading cause of maternal deaths in Australia and it is possible that there may be under-reporting of these occurrences. It is worthwhile noting that there were no deaths in this triennium from termination of pregnancy procedures.

For the first time, the national report for the triennium 2003-2005 did not include any clinical commentary or practice recommendations. It was considered, by the Australian Commission on Quality and Safety, (rightly, in my view) that because of inconsistencies and quality in the reporting from individual States and Territories, no meaningful conclusions or recommendations could or should be made. Until there is a uniform, consistent approach by a single central, properly authorised confidential committee, no valid clinical conclusions or recommendations are possible, which puts Australia far behind the process undertaken by the UK Confidential Enquiry into Maternal and Child Health.1

However, isn’t this good news, that the numbers in Australia are very small and appear to be declining? Well, surely that is so, but as is so often the case, a superficial look at the data doesn’t tell you the whole story, and there are several reasons to be concerned about maternal mortality and morbidity in Australia.

We need first to ask, how good are the data? There is a concern about under-ascertainment. As distinct from a stillbirth or a neonatal death, there is no mandatory notification of maternal mortality, although some States and Territories have a ‘tick box’ for notification that the deceased has been pregnant within the preceding 12 months. It is generally held that in the absence of coordinated efforts to maximise ascertainment, maternal deaths are underestimated by as much as 30 per cent. Some States undertake such efforts, but as is so often the case in public health surveys in Australia, there is variation between States and Territories in the approach to ascertainment. Failure to notify might be more likely for deaths in early pregnancy and when the death occurs remotely in time and/or place from the birth or termination of the pregnancy.

There is also variation and inconsistency in the way in which maternal mortality committees function in Australia, with respect to consideration, classification and reporting of maternal deaths. For example, in the compilation of the most recent report on maternal deaths in Australia, it appeared that there was no functioning maternal mortality committee in Queensland, which was the State with the highest MMR in Australia (over the previous twelve years).2 Only some States consider and report on preventability. Other States refrain because of privacy or other concerns. There are also variations in referrals of these deaths for coronial investigation. From 2003 to 2005, only 47 of 65 deaths were reported to the coroner, and only 19 of the 29 direct deaths were referred to the coroner.2

There are also concerns about the quality of data indicating Indigenous status. In the 2003 to 2005 report, data on Indigenous status was missing in eight per cent of maternal deaths. This deficiency is of special importance because the MMR for Indigenous women was 21.5, compared with 7.9 per 100,000 for non-Indigenous women, reflecting their health disadvantage, in pregnancy and childbirth, as it is in all areas of health of Indigenous groups.

There are other good reasons why we need a systematic national approach to identify, consider and report on causation of maternal mortality. The risk profile of women giving birth is changing. Obstetricians, general practitioners and midwives are now dealing with:

- older women embarking on pregnancy, particularly older/nulliparae, who are more likely to have underlying cardiovascular disease;

- more pregnancies as a result of assisted reproduction techniques, especially more multiple pregnancies;

- more obesity3;

- more hypertensive disease;

- more gestational diabetes; and

- more thrombo-embolism.

Furthermore, there are more women entering pregnancy with a history of prior caesarean sections, with the attendant risks of placenta praevia and placenta accreta, and severe peripartum haemorrhage.

It is estimated that for every maternal death, there are approximately 80 instances of severe maternal morbidity, in which the woman experiences a life-threatening complication from which she survives (completely, or sometimes with residual injury).4 Such severe morbidities include haemorrhage requiring blood transfusion, uterine rupture, eclampsia, renal failure and other conditions involving transfer to a designated intensive care unit.

In acknowledgement of the importance of addressing severe maternal morbidity, in 2008, the Australian National Health and Medical Research Council funded the establishment of the Australian Maternity Outcomes Surveillance System (AMOSS), based at the Perinatal and Reproductive Epidemiology Research Unit at the University of New South Wales. AMOSS will collect data on a range of serious but rare complications and disorders of pregnancy, which are thought to contribute significantly to the burden of maternal morbidity in Australia. This will add significantly to our understanding of risks and complications of pregnancy, and will advise clinicians about these risks and how the occurrences may be reduced.

A concerning aspect of maternal mortality monitoring in Australia is the lack of recurrent funding or a permanent auspicing agency. The last national maternal mortality report carried a foreword signed by the Director of the Australian Institute of Health and Welfare (AIHW), which auspiced and authorised the report that contained this statement:

‘..the (Australian) Commission (on Safety and Quality in Health Care) is not able to provide ongoing funding (for regular reporting of maternal deaths in Australia) and it is concerning that no resources have been identified to sustain and improve this reporting in the future.’

An options paper to obtain a firm footing for the national maternal mortality survey has been prepared by the AIHW and submitted to the Commission on Safety and Quality in Health Care, but no response had been received at the time of preparing this article.

Given the profound tragedy of the death of a woman in pregnancy, childbirth or the puerperium, and the ripple effect such an event has on the immediate and extended family, even to the next generation, surely Australia should be able to proudly proclaim that it takes these occurrences extremely seriously, that it has a consistent, comprehensive approach to ascertainment, confidential enquiry and reporting of maternal deaths, with consideration of all instances by a legally mandated and protected panel of experts. The recommendations of this panel should be available to policy makers, funders and providers of healthcare for pregnant women, as well as to the public, so that we can reassure the childbearing population and their relatives that every effort is made to prevent these catastrophic events.

References

- Lewis G, Ed. The Confidential Enquiry into Maternal and Child Health (CEMACH). Saving Mothers’ Lives: reviewing maternal deaths to make motherhood safer 2003-2005. The seventh report on confidential enquiries into maternal deaths in the United Kingdom. London. CEMACH 2007. See: www.cemach.org.uk (last accessed 2009).

- Sullivan EA, Hall B, King JF. Maternal deaths in Australia 2003-2005. Maternal Deaths Series No. 3 Cat. no. PER 42. Sydney: AIHW National Perinatal Statistics Unit. (See: www.npsu.unsw.edu.au NPSUweb.nsf/resources/MD3/$file/md3a.pdf).

- Maternal Mortality in 2005. Estimates developed by WHO, UNICEF, UNFPA and the World Bank. Geneva: WHO, 2007. See: www.who.int/reproductive health

- O&G Magazine, Vol 10, No 4 Summer 2008.

- Murphy C, et al. Severe maternal morbidity for 2004 2005 in the three Dublin maternity hospitals. Eur J Obstet Gynecol. (2009) doi: 10.1016/j.ejogrb.2008.11.008.

Leave a Reply