Most Australian health professionals are aware that health indicators for Indigenous Australians are much worse than national averages. Indeed, there have been regular ABC televised programs on the subject during 2008. However, just north of Cape York Peninsula and literally only a few metres from Queensland, health issues are much worse than most Australian health professionals could even imagine.

It is an accident of history, based somewhere in the meanderings of Captain Cook and other 17th and 18th century maritime explorers, that the current border of Australia passes through the narrow stretch of water that we call the Torres Strait. One can actually see Papua New Guinea (PNG) from the northern most islands of the Torres Strait.

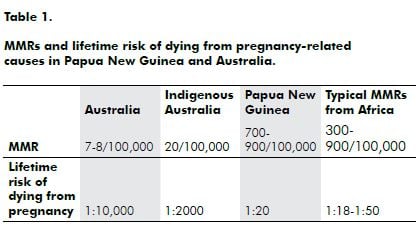

The public health parameter that shows the widest discrepancy between developed and resource poor countries is the maternal mortality ratio (MMR). This is the number of women who die (per year) from pregnancy-related causes per 100,000 live births.

The MMR in Australia has been less than 10/100,000 for the past several decades. In fact, recently, it is has been mooted that, because hardly any women die from maternal deaths anymore, that the committee which was set up after the Second World War to annually examine maternal deaths and produce a triennial report to the Government, be disbanded because of insufficient activity. On the other hand, the MMR in Papua New Guinea runs into the hundreds. The MMR for Indigenous Australians usually runs at about two to three times that for non-Indigenous Australians, therefore 20/100,000.

In 1996, a demographic health survey (DHS) calculated the MMR in PNG to be 370 and the latest DHS (2006) has found it to have increased to 733. In the 1970s and 1980s, the World Health Organization (WHO) drew up a mathematical model to assist developing countries in working out what their MMR might be. It is notoriously difficult to accurately measure the MMR in a country that does not have quality vital registration systems. The figure that the WHO MMR predictive model calculated for PNG was 900!

These sorts of figures mean that a young woman in PNG has to consider that her lifetime risk of dying from a pregnancy-related cause is about one in 20, whereas the lifetime risk of an Australian woman dying from a pregnancy-related cause is probably about one in 10,000 (for Indigenous Australian women about one in 2000). Therefore, the relative risk of dying from pregnancy-related issues is 500 times more likely in PNG than it is in Australia (see Table 1). The PNG figures make for a completely different attitude torwards pregnancy and risk in the minds of ordinary people. In Australia, most women would not even consider it a possibility that they could die from a pregnancy complication, whereas in PNG, every woman knows someone who has died from a pregnancy-related problem. In every class of school girls, there will be at least two who will die from a pregnancy-related cause during their lifetimes.

The demographic perspective for doctors and midwives is also quite different. Most doctors and midwives in Australia would not expect to see a maternal death in their whole professional life. Whereas in PNG, in a busy maternity unit (like that of the Port Moresby General Hospital where we have about 12,000 births per year), we can expect to see a maternal death once or twice a month. Thus, medical students and residents see several maternal deaths during their training period. Indeed, in the compulsory four-month O and G intern block, a resident could expect to see eight maternal deaths.

Why is it that so many women die from pregnancy- related causes in developing countries?

The MMR is not only the public health parameter that indicates the most discrepancy between developed and developing countries, it is also the most sensitive indicator of the quality and total functionality of the healthcare system of a country, as well as the socio-economic status of the community in a global sense.

For example, infant mortality rates (IMRs) in developing countries typically range between 40 and 90/1000 children for the first year of life. Developed countries typically have IMR figures of the magnitude of 10 to 20/1000. The IMR difference between countries like Australia and PNG is about five times (compared to 5000 times for the MMR difference). This is because simple public health measures (such as immunisation, exclusive breastfeeding, water, sanitation and primary healthcare access for illness treatment) can keep the majority of babies safe and healthy. Parents will take their sick children to the best facility that they can access when problems arise, even if this requires quite extensive travelling away from home. Babies are also quite portable.

Pregnancy care, on the other hand (particularly when it comes to complications that can kill), requires emergency obstetric care capacity and community infrastructure access (roads, bridges and vehicles) to get the woman to the emergency care facilty. Pregnant women are not so portable, particularly when they are in labour or bleeding postpartum. Time is also of the essence. A woman with a serious pregnancy complication (for example, postpartum haemorrhage or a ruptured uterus) can die within the hour.

Actual risk is also related to how many times you ‘run the risk’. In Australia today, the total fertility rate (TFR), therefore, the total number of children a woman has in a lifetime is 1.8, whereas in PNG the TFR is over four. So it is much more dangerous for women to have a pregnancy in PNG and they are running the risk more than twice as often as Australian women.

The maternity care situation in Papua New Guinea

Most women do attend some kind of antenatal care (nationally about 60 per cent of women book at an antenatal clinic) at least once during their pregnancy, but many rural clinics are not able to do tests or provide detailed checks, nor are they are able to easily refer women when a problem is discovered. Only 38 per cent of women in PNG have a professionally supervised birth. This means that 62 per cent of women have their baby at home with only their mother or another female relative to care for them. A significant proportion of women (ten per cent) deliver their baby absolutely alone.

Professionally supervised birth with expeditious access to emergency obstetric care is the single most important way of preventing women from dying with pregnancy-related complications. In PNG, this necessarily means having your baby in one of the better health facilities, where there is the realistic possibility of referral to a provincial hospital if something goes wrong.

In a study done in the mostly rural Simbu province in 19831, it was found that the MMR amongst women who had a village birth was 400. The MMR for women who had a facility supervised birth was 100.

The other thing that will make all the difference to the appalling maternal mortality situation in PNG is the demographic transition. In my professional career, the TFR has come down from six (1968), to 4.8 (1996) to 4.4 today. However, because of a major and long-standing epidemic of sexually transmitted infections in PNG, pelvic inflammatory disease is the commonest gynaecological problem that we see in clinics and of course this is associated with a high level of infertility due to tubal factors. This means that the average TFR of women who are not infertile is still nearly five. Our demographic health survey also shows that, by and large, women have one more baby than their ideal or desired family size. Unplanned high parity pregnancies are one of the major associations with maternal death in PNG. Family planning not only has social and economic benefits for most families in PNG, it can also be life-saving.

Effects on families, health workers, politicians and policy makers

The effect on a family is of course devastating. Older women with many children leave a number of children with no mother. These children are often distributed amongst relatives to look after, particularly if they are young. Older children may stay with their father. However, young primigravidas can be forgotten quite quickly. Men usually remarry after a few years and the children of the mother who has died can then be even more socially displaced. In developing countries, there are often no special counselling facilities available to assist health workers who have had to cope with a maternal death. At Port Moresby General Hospital, there is always a detailed audit process and junior staff are helped to understand about what we could not have done any better and those aspects of care which we could have done better.

Unfortunately, politicians and policy makers have yet to come to grips with this issue.

A young woman dies

The first maternal death this year at Port Moresby General Hospital was a young woman having her third baby. The first baby had been delivered by caesarean section (CS) when she had a persistent breech presentation at term. In the second confinement, she failed ‘the trial of scar’ and a repeat CS was performed. In this pregnancy, an elective CS was booked at term, but she came into labour on the Sunday morning before her booked operation. She was taken for a repeat CS by a senior registrar. Some four hours after the operation, she was found to have dropped in blood pressure and the duty consultant considered that there was blood in the peritoneal cavity. She was resuscitated with IV normal saline, but there was no blood of her type available in the blood bank. On return to theatre, she was given a general anaesthetic by the duty anaesthetic registrar because of the emergency situation, but she had a bad chest and there was difficulty with oxygen saturations. She had a cardiac arrest in the recovery area and died a few days later from a combination of renal and respiratory failure.

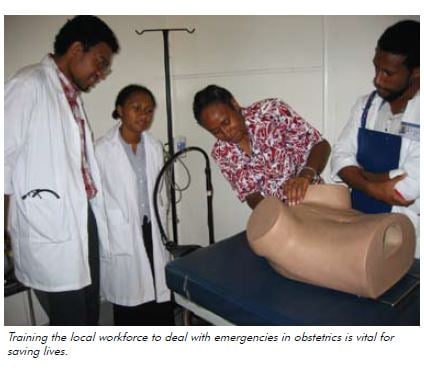

its very important to train any health workers with emergency skills and knowledge because emergency is a situation in which it needs urgents and active management within less than some minutes. therefore, i would encourage every health workers must be trained with emergency skills and knowledge in every health facility so the with knowledge and skills can be able to save many lives whenever they come across.

Working in the Solomon Islands in the 1970’s and later in the Kimberley Region of Western Australia in the 1980’s I saw no maternal deaths though responsible in my regions for several thousand deliveries in this period. The outreach of experienced health professionals on a regular touring basis to all villages, no matter how remote, to provide antenatal assessments, screen and arrange early referral to appropriate hospital care was I believe the most important factor in reduction of maternal deaths.